THE RED MAN AND HELPER

NINETEENTH YEAR OR VOL. XIX NO. 33

FRIDAY, MARCH 18, 1904

PRINTED EVERY FRIDAY BY APPRENTICES AT THE INDIAN INDUSTRIAL SCHOOL,

CARLISLE PA.

A MEETING OF FORMER FOES

THE RED MAN AND HELPER

NINETEENTH YEAR OR VOL. XIX NO. 33

FRIDAY, MARCH 18, 1904

There has been a larger demand for our Commencement number,

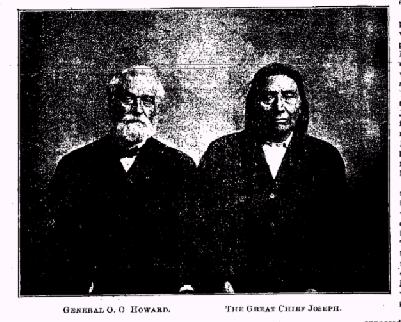

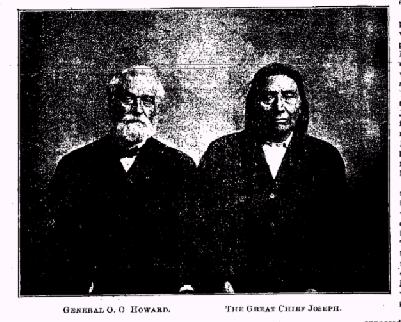

containing General Howard's and Chief Joseph's picture, than we can supply,

hence we print the pictures again. They are both noble veterans whose

kindly faces are worthy of a second study:

A striking incident of the anniversary exercises at the

Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pa., last month, is set forth in

the RED MAN AND HELPER, the school publication, just at hand. This

was the presence of Gen O.O. Howard and Joseph, chief of the Nez Perces

the commander in a most remarkable Indian war, of which Gen. Howard has

written in his book, "Chief Joseph of the Nez Perces in Peace and War."

The official accounts characterize that as "one of the most extraordinary

Indian wars of which there "is any record," because of the courage and

skill displayed by the Indians. They abstained from scalping, let

the captive women go free, did not commit indiscriminate murder of peaceful

families, as was usual in such warfare, and fought with rear guards, skirmish

lines and field fortifications.

The meeting of the two leaders in that war 27 years after

it ended in Chief Joseph's suppression, and the things they said to the

Indian boys and girls at Carlisle, make a picture out of the ordinary.

Thus Gen. Howard said: --

"There are no people we honor more than we do the Indians. You will say, 'But didn't you fight the Indians?' Yes. I am an army officer. I would fight you if you rose up against the flag. I want it understood that when I fought with Joseph I was ordered by the government at Washington to take Joseph and his Indians to the reservation that was set aside for them. Joseph said he would not go on any reservation. A majority of the band had agreed to leave and go to the place designated. But Joseph and White Bird and Looking Glass were left out. They did not understand that a majority rules. They would not agree to be ignored and left out in the division of land when the best of it was to go to someone else. After the Indians accepted the reservation the government of the United States reduced it and reduced it again, and the Indians rebelled and I was sent to carry out the government's instructions. I could not do otherwise. I did my best to perform the duty. Some would not come. I understood the reason then. But it is all past. It took a great war. I would have done anything to avoid the war, even to giving my life. But the time had come when we had to fight. There come times when a fight is a mighty good thing and when it is over let's lay down all our feelings and look up to God and see if we cannot get a better basis on which to live and work together."

Col. Pratt, the head of the school, in calling out the other leader, said: "I present to you Chief Joseph of the Nez Perces in Washington. Gen Howard and Joseph fought each other in '77, two years before Carlisle began. Their line of battle was 1400 miles long. We think Gettysburg a big battlefield, and we are proud of it. Joseph would not go on his reservation, and had his way for a time. He really never did go there. I have always regarded Chief Joseph as one of our great Indians. He kept ahead of Gen. Howard for 1400 miles." THE RED MAN AND HELPER prints pictures of Howard and Joseph, sitting side by side. The speech of the Indian, as interpreted to the audience, was as follows: ---

"Friends, I meet here my friend, Gen. Howard. I used to be so anxious to meet him. I wanted to kill him in war. Today I am glad to meet him, and glad to meet everybody here, and to be friends with Gen. Howard. We are both old men, still we live and I am glad. We both fought in many wars and we are both alive. Ever since the war I have made up my mind to be friendly to the whites and to everybody. I wish you, my friends, would believe me as I believe myself in my heart in what I say. When my friend, Gen. Howard, and I fought together, I had no idea that we would ever sit down to a meal together, as today, but we have and I am glad. I have lost many friends and many men, women and children, but I have no grievance against any of the white people, Gen. Howard or any one. If Gen. Howard dies first, of course I will be sorry. I understand and I know that learning of books is a nice thing, and I have some children here in school from my tribe that are trying to learn something, and I am thankful to know there are some of my children here struggling to learn the white man's ways and his books. I repeat again I have no enmity against anybody. I want to be friends to everybody. I wish my children would learn more and more every day, so they can mingle with the white people and do business with them as well as anybody else. I shall try to get Indians to send their children to school."

Not always has Chief Joseph been of this mind. The

white man has kept him moving, and he has been philosopher enough to accept

that which he must. He belonged to the non-treaty band of the Nez

Perces, which occupied the Wallowa reservation in Oregon, and opposed the

introduction of schools there. Interrogated regarding this attitude,

he replied:---

"No, we do not want schools or schoolhouses on the Wallowa

reservation."

"Why do you not want schools?" asked the commission.

"They will teach us to have churches."

"And why do you not want churches?"

"They will teach us to quarrel about God, as the Catholics

and Protestants do on the Nez Perce reservation and other places.

We do not want to learn that. We may quarrel with men sometimes,

but we never quarrel about God. We do not want to learn that."

The observation of the untutored red man was disconcertingly

keen, to be sure. But time has taught Chief Joseph to bow to the

inevitable. He now accepts the situation as the white man has made

it:

"I wish my children would learn more and more every day,

so they can mingle with the white man and do business with them, as well

as anybody else." It is the only way of salvation left for the Indians

who are to follow - and a very straight and narrow way at that.

| CHIEF JOSEPH, interpreted by James Stewart.

Friends, I meet here my friend General Howard. I used to be so anxious to meet him. I wanted to kill him in war. Today I am glad to meet him, and glad to meet everybody here and to be friends with General Howard. We are both old men, still we live and I am glad. We both fought in many wars and we are both alive. Ever since the war I have made up my mind to be friendly to the whites and to everybody. I wish you, my friends, would believe me as I believe myself in my heart in what I say. When my friend General Howard and I fought together, I had no idea that we would ever sit down to a meal together, as today, but we have and I am glad. I have lost many friends and many men, women and children, but I have no grievance against any of the white people, General Howard or any one. If General Howard dies first, of course I will be sorry. I understand and I know that the learning of books is a nice thing, and I have some children here in school from my tribe that are trying to learn something, and I am thankful to know there are some of my children here that are struggling to learn the white man's ways and his books. I repeat again I have no enmity against anybody. I want to be friends to everybody. I wish my children would learn more and more every day, so they can mingle with the white people and do business with them, as well as anybody else. I shall try to get Indians to send their children to school. That is all I can say tonight. |

| COL PRATT: I also had an experience with Joseph. After he was captured,

Joseph and his people were sent down to Ft. Leavenworth, to be held as

prisoners, and Gen. Armstrong wanted fifty more Indian children at Hampton.

I was up in New York at the time and the Secretary of War sent for me to

go to Joseph and arrange for the transfer of that number of his children.

General Pope, and then Major now Gen. Randall, had brought the subject

to Joseph before I got there and he had fixed his mind against it.

Joseph said he would not let the children go anywhere until he knew what the Government was going to do with him. Of course we did not want to force him to give up his children. That was 27 years ago. You see how he had changed his mind. I met him six or seven years ago over in eastern Washington, at his old home where he was then visiting. He was attending a gathering of the Indians and I supposed this man whom I thought one of the greatest of their people, would be one of the first to speak, but there seemed to be some objections to his speaking. I felt sorry for him and am glad he came here. We have much sympathy for him. He has been a great heroic man in his way and has been through great trouble. He is now on the Colville reservation not far from his old home. I wish something might be done for him. |

| HOME | History | Virtual Tour | Primary Sources | Secondary Sources | Biographies |

| Jim Thorpe | Related Links | Powwow 2000 | List by Nation | Problematic Historical Fiction | Photo List |